Featured In The Franciscan Way Magazine: Spring 2025

Father Colin King, OFM, realized that the Franciscan mission based at the Mary Gate of Heaven Roman Catholic Church in Negril, Jamaica, was having a significant impact after an incident that occurred when he had been there for a few years.

He was on a home visit to one of the three mission parishes served by the Negril parish. Deep in the underbrush lived a blind, elderly woman. After the visit, he emerged in a white Franciscan habit, walking towards a soccer field where a group of boys was kicking a ball around.

“Oh, it’s Jesus,” they cried, pointing to the American friar trudging through the bush. Father Colin doesn’t suffer from messianic impulses, although he loves the connection the boys made. The identification signaled a deeper reality. “People know who we are. We are here for the community,” he said.

The friars are known around Negril, in the far western reaches of the island, for serving a largely non-Catholic community that struggles with poverty and survival, in a region known for its verdant greenery and beaches that attract tourists from all over. Jamaica has always been an island nation of contrasts.

The friars have a long but interrupted history there. The first Franciscans arrived with Christopher Columbus.

The island changed from Spanis hto British control, and for long periods Catholic practice was banned by colonial authorities.

The people are largely a mix of descendants of British colonist, Africans, and East Asians who were brought in to work the sugar fields. The British colonial legacy hangs over the island nation.

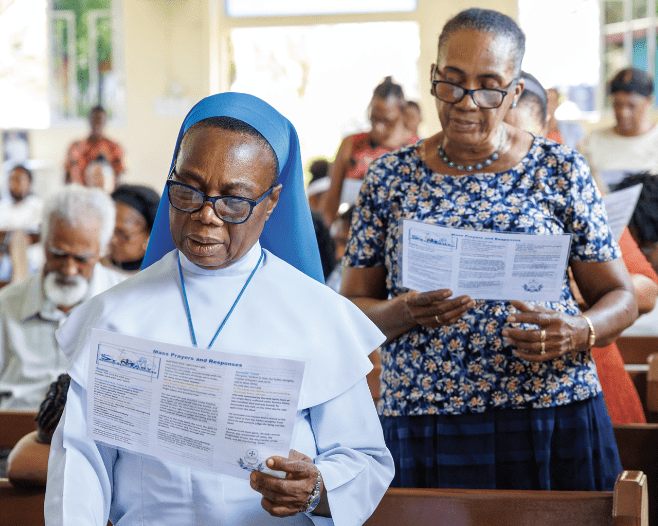

It is estimated that only about two percent of the people are Catholics, with most belonging to the Anglican Church or emerging evangelical congregations.

The island gained independence from Britain in 1962.

“It’s still a young country,” said Father Colin.

Friars from the legacy province of St. John the Baptist, based in Cincinnati, now a part of the wider Our Lady of Guadalupe Province, came to the island in 2000 to assist the Diocese of Montego Bay. The small Catholic community of Negril and its surrounding missions is active and outer-focused.

While the universal church is implementing the concept of synodality in decision making, Catholics in rural Jamaica have long experience with shared responsibility.

“The Church has needed strong lay leadership to survive,” said Father Colin, noting long periodswhere there were few priests in the region.

The parish regularly reaches Catholics and non-Catholics. One area of concern is education. “In Jamaica, education is free, if you can afford it,” said Father Colin.

Grinding poverty is a fact of life, and parents struggle to pay transportation costs and school uniform fees. In response, the friars sponsor a Get Kids to School Program.

More than 100 children are assisted by a bus to school and supplied with backpacks, books and pens.

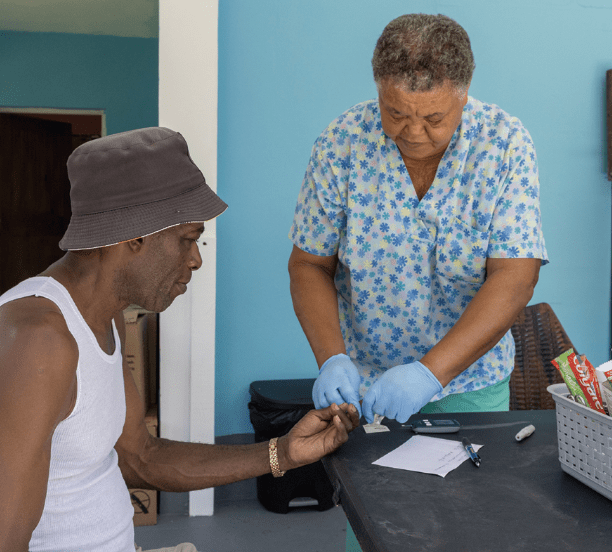

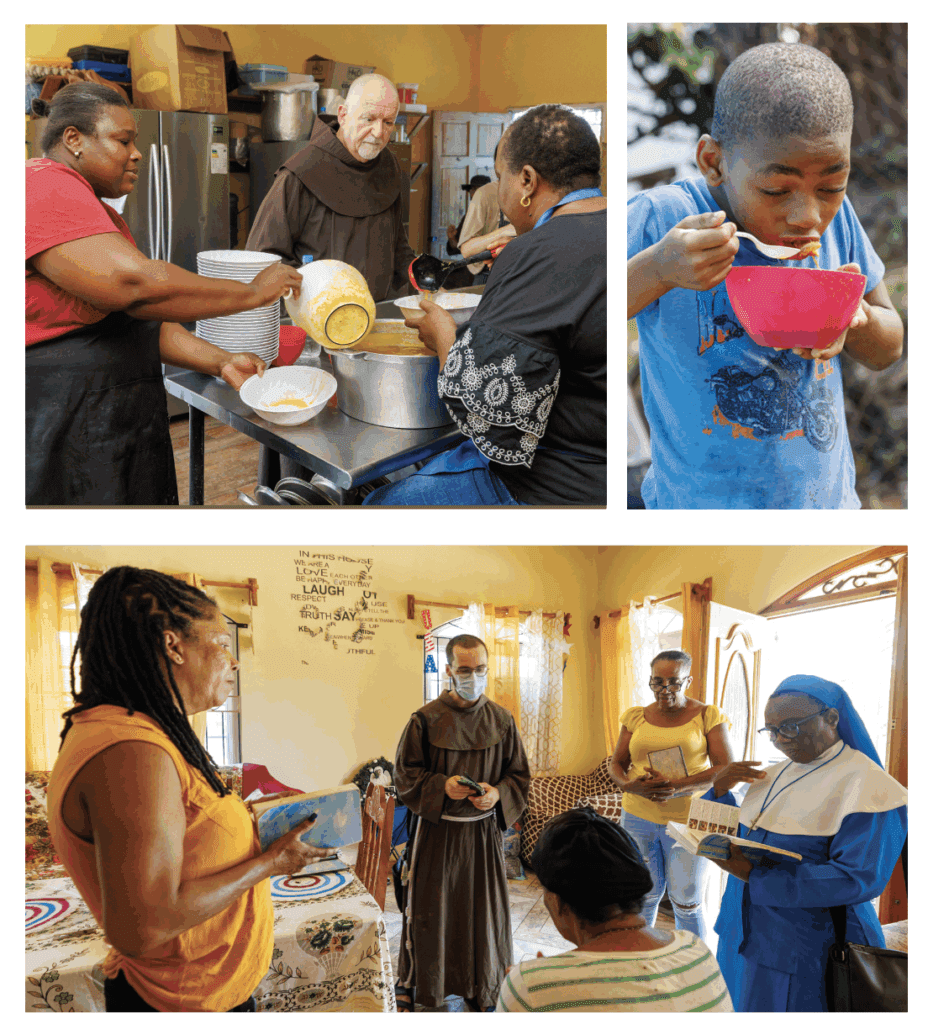

The mission also supports a medical clinic. And the St. Anthony Soup Kitchen helps all comers, serving hundreds each day without regard to religious affiliation.

One source of financial support for the mission is tourists, who venture out from the local resorts to attend Mass and return regularly, sometimes volunteering or providing donations.

The soup kitchen differs from those sponsored by other denominations, which require allegiance to a creed.

Father Colin pointed out that Jesus didn’t ask about synagogue attendance when he fed the crowds.

Brother Tim Lamb, OFM, a New Hampshire native, has spentfour years in Jamaica, tasked with overseeing the mission’s finances and leading orientation for new friars, as well as running the St. Anthony Soup Kitchen.

On the night he was interviewed, Brother Tim was also taking care of five puppies bequeathed to the friary after their mother was killed in a car crash. They were barking and jumpy, as the friars pitched in until the dogs could be placed in homes.

The Franciscan mission has become known for caring for animals as well as poor people, following the legacy of St. Francis of Assisi. At the St. Anthony Soup Kitchen, about 150 patrons are fed every day. Some are new arrivals; others have been regulars for years, some suffering from drug addiction or HIV/AIDS, as well as the poor and elderly.

The goal is personal service.

“I say hello to them. It is a way I learn their names. I sometimes sit with them when they come to eat,” says Brother Tim.

When visiting friars come to the mission, Brother Tim also orients them to the area, emphasizing the value of listening. That can sometimes be difficult.

While English is the official language, many of the people, particularly those in the hills, speak a patois, often indecipherable to most Americans. Father Colin knows that when the people don’t want him to understand what they are talking about, they will speak in patois, which combines African languages with English, Spanish and French.

The soup kitchen ministry and education outreach were led by Father Jim Bok, OFM, who returned to Ohio in 2023 after spending 16 years in Jamaica, becoming an instrumental part of the mission’s history.

An educator himself, Father Jim wanted the mission to meet as many needs as possible. For example, he noted in an appeal video that nutrition is a vitalcomponent of learning. “A hungry child does not learn,” he said.

Another friar currently serving at the mission is Brother Richard Gaunt, OFM, a newly-professed friar who cycling through to learn about ministering in mission.

He is part of Brothers Walking Together, a program introducing newly-professed friars to ministry among the poor before they begin their theological studies.

Brother Richard arrived in Negril in the summer of 2024, a month and a half after professing first vows. “One of the challenges of coming here is that it’s a totally new context. I had never been to Jamaica, and I didn’t know much about it when I arrived, so there was a lot to get used to and a lot to learn. The brothers did a good job of showing me around when I arrived, introducing me to different people and orienting me to the ministries here,” said Brother Richard.

Brothers Walking Together has helped Brother Richard realize that God is calling him to the priesthood. That was not something he was entirely sure of in the novitiate. “I know other brothers have come here and found the opposite; they may have been considering the priesthood, but they have discovered their gifts in ways that have led them more to a brother vocation instead,” said Brother Richard.

Some of the ministries Brother Richard is engaged in in Jamaica include home visits to the homebound, assisting at the St. Anthony Soup Kitchen, and tutoring children in reading and writing.

“Literacy is a big issue here. A lot of the kids grow up without learning how to do basic reading and writing,” said Brother Richard.

He’s discovered that in Jamaica, women play a major role in running families. “Children are sometimes left lacking strong male role models in their lives,” he said. “The importance of having us friars come into the lives of the Jamaican people is that we offer them God’s unconditional love, set the example of what honest and kind men should be.”

To many tourists, life in Jamaica consists of sunny days and stress-free winters. Yet the friars learn quickly that the environment is often not so friendly.

“In the island, we share the same environmental struggles, including hurricanes, floods, loss of electricity, heat and mosquito-borne illnesses,” said Brother Richard.

In western Jamaica, people rely on low-paying jobs in the region’s tourist industry, catering to foreigners in all-inclusive resorts.

Father Colin has been coming to Jamaica since a mission trip during his seminary years.

He’s found the island nation a place to identify with Francis’ mission to the poor. He’s baptized the baby of a prostitute who came with a request that she wanted her infant to experience Christian faith. He’s presided over the funeral of a 25-year-old woman who died in childbirth. Everyday life presents its regular struggles.

The rural areas have no piped in source of water, so the people gather rainwater.

Even in the town, there is no public transportation for the children to get to school.

The struggles of the people contribute to an intense faith life and reliance on God to help with physical and emotional needs. Sunday Mass lasts nearly two hours.

Praise and worship

Parishioners expect longer homilies than those that are routine in the U.S. In seminary, Father Colin was told to keep homilies to seven minutes. With his Jamaican flock, a sermon that short causes concern that their parish priest must be ill. And singing is required.

Father Colin claims to have little rhythm and a terrible singing voice. “But everyone here sings, whether you are a good singer or not. It’s about praising God.”

Much of his ministry is about walking with those in distress. Jamaica has some 2.9 million people. But almost as many with roots on the island are part of the diaspora, settling in the U.S., Britain and continental Europe, among other places, seeking, for the most part, a way out of the island’s poverty.

More than a million Jamaicans reside in the U.S., most of them in Florida and New York.

A typical recent day had Father Colin praying with an elderly woman whose daughter was in Switzerland experiencing a problem pregnancy. She felt helpless, unable to render much assistance. Prayer was the only option for her and was what she needed.

Challenges like that pop up regularly at the Franciscan mission. For Father Colin, it’s part of the privilege of being a Franciscan, being with people who regularly suffer heartache and need, tempered with a deep faith.

“For me, Jamaica allows my Franciscan vision to come alive. It’s a great place for us to be. We serve people who are easily forgotten. If we didn’t do it, would not happen,” he said